Nicholas Ray was the son of a lumber magnate and grew up in rural Wisconsin. He enjoyed a middle-class upbringing, coming from a wealthy and ostentatiously, at least, strictly religious family. However Ray’s father was excommunicated from the local diocese for his many affairs and his heavy drinking. Despite performing well at school, Ray had an unconventional childhood: he began drinking at the age of ten, becoming involved in the seedy underworld of a seemingly idyllic village and even tried to seduce one of his father’s lovers at the age of thirteen. Ray was arrested at seventeen for allegedly trying to run over Doc Rhodes, the physician who had attended his dying father, and the person he blamed for administering medication which caused his death. Ray’s main biographer Bernard Eisenschitz claims that this event sowed the seeds for his later scepticism towards medicine and the medical establishment as whole, which is expressed in Bigger Than Life. Also, this chaotic family upbringing can be interpreted as being the reason behind Ray’s scathing attacks on middle-class American lifestyle and morality, something which is also present in Bigger Than Life.

Ray became interested in theatre at an early age, and moved to Chicago to study it there. Here he met the architect Frank Lloyd Wright and the writer Thornton Wilder. The former invited him to his artistic and intellectual project the Taliesin Fellowship. Named after the Welsh bard (Lloyd-Wright identified himself as Welsh-American, and aimed to forge this into a stable ethnic and cultural identity), its aim was to propose a new way of thinking about the world and a new approach to learning, one which (in the words he used in a self published circular) would ‘develop a well-correlated human being: since correlation between hand and the mind’s eye in action is most lacking in modern education.’

The fellowship was based on an isolated farm in the same Wisconsin countryside Ray knew well from his childhood. Spending nearly a year there, he was asked to leave thanks to his heavy drinking and drug taking. According to his ex partner Jean Evans, a ‘vindictive and moralistic’ Wright also took issue with Ray’s bisexuality and they severed contact when Ray left for Mexico in 1934. Thorton Wilder’s existentialism was something which attracted Ray, who himself kept books by writers like Dostyevski, Camus, and Satre, alongside works by modernist writers like Joyce and Thomas Mann, and the theatre of Brecht. However, the confines of university education also proved too much for the rebellious young director, and he lasted six months at the University of Chicago before moving to New York to work in radio and begin his professional involvement with drama.

In the ‘Big Apple’ Ray made the acquaintance of Turkish director Elia Kazan, who at this point was striking success with his own theatre company, and ‘Gadge, as he was known to friends, introduced Ray to the NY theatre scene. This period of his life, spent in the heart of Greenwich Village, was a raucous one. Through his work in broadcasting and his involvement with theatre groups inspired by the works of Marxist writers like Brecht and Shaw, Ray met figures like the folk singer and political activist Woody Guthrie, the self styled founder of jazz Jelly Roll Morton, as well as the musician Duke Ellington with whom he worked on what was to be Ray’s only Broadway production.

The cosmopolitan New York, with theatres and nightclubs which were beginning to defy segregation norms and allow entry to non white people, saw the emergence of African-American voices in popular culture and also the establishment of a working-class identity in the mainstream. This captured Ray’s imagination, and led to a social consciousness and political awareness which was to determine his next career move: Ray became involved with government art projects ushered in by Roosevelt’s New Deal. Ray was placed in charge of an unprecedented and never repeated move by the federal government: to support and fund theatre, painting, independent film, and even the plastic arts. This task led him to travel the country and experience firsthand the effects of the depression, and the anger felt by many towards the government’s failure to deal with the problems incurred by the economic slump seen in the wake of the 1929 crash.

This also led to a brief spell as a member of the communist party, something that would later threaten his career as a filmmaker during the ‘Red Scare’ of the fifties. Ray himself claims that it was only thanks to the efforts of the eccentric millionaire media mogul and celebrated aviator Howard Hughes, who was at that time owner of RKO Pictures, the production house that Ray was contracted to during the fifties, that he was able to avoid being called up in front of the House of Un-American Activities and risk being blacklisted as a Hollywood director. Even so, a brutal decade of producing nearly a film a year took its toll on Ray and he collapsed on set of the Charlton Heston vehicle 55 Days in Peking, and this ended his career as a commercial filmmaker.

Nicholas Ray’s life was full of paradoxes, like the America in which he lived. A brawler, heavy drinker and playboy, he seemed to epitomise on the one hand a certain ideal of American masculinity. However, on the other hand, his drug taking and bisexuality defied his becoming an all American caricature. And his socialist ideals, held even whilst he worked in an aggressively conservative and rampantly capitalist film industry led to these paradoxes being weaved and spun into the films he made. Ray was able, alongside filmmakers like Samuel Fuller and Douglas Sirk, to adhere to the rules of the conservative motion picture production code, otherwise known as the Breen or Hayes Office, yet at the same time subtly subvert these same rules which sought to promote a Christian and conservative view of the nuclear family and of an American society strongly committed to consumerism. Bigger Than Life is a great example of how a director is able to, with clever use of the medium, tell two stories at once, and is able to celebrate and criticise his subject matter simultaneously.

Shortly before his death on 15th June 1978, Nicholas Ray was quoted, after a screening of his last film, a collaborative project with the German New Wave director Wim Wenders, as saying that he had ‘dreams of being able to tell all of Dickens in one film, all of Dostoevsky in one film. I wondered if it was possible for one film to contain all of the aspects of human personality: needs, desires, expressions, wants…’ Does Ray achieve this ambitious project in his in his films? Perhaps one can think about this as one watches Bigger Than Life. Like his contemporaries Fritz Lang, Elia Kazan, and Howard Hawks, Ray, working in the Hollywood studio system’s Indian summer, was able to exercise an incredible amount of control over the content of his films. Also, given his background in theatre, Ray is clearly aware of the potential that cinematic techniques hold in producing meaning.

What is interesting about Nicholas Ray, and in particular this film is how it attracted the attention of a school of French critics writing for the influential film journal Cahiers du Cinema. Founded in 1951 by theatre critics André Bazin, Jacques Doniol-Valcroze, and Joseph-Marie Lo Duca, the journal wanted the relatively new medium of film to be recognized as an art, rather than simply filmed theatre. This became Cahiers du Cinema’s mission. Those who wrote for it tried to define new ways to discuss, criticize, and write about film, often analyzing films from big directors like Hitchcock, Capra, Welles, and Huston in terms of their technical qualities. Famously, this led to many of the Cahiers critics becoming filmmakers themselves, utilizing the concepts which they had created in their critical endeavours, and famously spearheading the 60s film movement the French New Wave: Francios Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, and Claude Chabrol all wrote for Cahiers and are only three names amongst many who successfully made the transition from film criticism to film production. Indeed, after the war, the embargo on Anglo-American culture in Paris was lifted, often leading to whole evenings showing works by one director. This perhaps can serve as an explanation for the rise of theorists who successfully identified signature touches by certain director’s, like Welles’ deep focus, or Max Ophul’s distinctive use of lighting.

Two things are important to note here. One, that in trying to gain respect for the new medium of film, these early film theorists gave the director the bulk of the credit for the production of meaning in a motion picture. Two, the director was viewed, rightly or wrongly, as having complete control over the set, the casting, the cinematography and all the other factors within the text which help to produce meaning. As earlier mentioned, this is perhaps not an incorrect assumption, because the studio system was created and structured in such a manner that allowed the director to have a large amount of creative control over the content of the film. Whether we can make the simple comparison between a director and the writer of a novel or a philosophic treatise is not easy to answer, but I have followed the lead of these auteur theorists in assuming that the director is responsible of the lion’s share of meaning within a film, especially within a film produced in the controlled environment of a Hollywood studio.

Furthermore, the Hollywood melodramas of Nicholas Ray attracted the attention of the French philosopher Gilles Deleuze. His work on film is split into two volumes: one dealing with the movement image and one which deals with the time image. For our purposes, we are concerned with the movement image and with two specific types of movement image: ones which express thoughts and feelings, and ones which are mimetic, that is to say, ones which attempt to be objectively, or purely representational. It is easiest to understand Deleuze’s distinction as the difference between the close-up and the mid shot: the close-up is deployed by a film maker to stir up feeling in an audience, whilst the mid shot depicts action, distances the audience from the image and enables a viewer to take in action with more of God’s eye view. They are no longer immersed in the feelings of the characters they perceive, but are more concerned with the distances between bodies which enables actions like those seen in fight scenes or shootouts to be understood in spatial terms.

According to Deleuze, Ray’s development as a filmmaker can be understood as a progression from the representational to the expressive, from a form of cinema which attempts to be mimetic to one which is lyrical. This is why he claims that Ray’s films shift from the naturalist tradition seen in theatre, which is constantly viewed by an audience in a static mid shot, and utilised by directors like Sirk and Kazan who began treading the boards before becoming directors, towards lyrical abstraction which comes with Ray’s later work, of which Bigger Than Life is a prime example. Thus, Bigger Than Life can be viewed as a film which attempts to break from naturalist representationalism towards a more complex use of the visual image, one which is aware of itself as medium and furthermore, one which is able to, like the lyric, express extremely complex meaning.

Deleuze’s two volumes on the ontology of cinema are heavily influenced by auteur theory, and thus on the assumption that the director, in this case Nicholas Ray, is the locus for the production of meaning in a film. We can draw a conclusion from this: film is a controlled world, like that an author creates in a novel, and reading it as simply being mimetic is a perhaps a naïve mistake. Rather, the film, like the written text of a fiction writer, addresses certain concerns that the director has, and even though the director may be constricted by a production environment, a screenplay which he hasn’t written, and even a hostile political landscape, he is, through the clever use of the medium, able to work these concerns into the work he is in charge of producing – even if those concerns are unpalatable to the audience it addresses. I think Bigger Than Life is an excellent example of this.

I’d like to say a few things about the iconography and one major issue which seems to have divided critics about the film, and couch this in terms of the existential philosophy that Nicholas Ray was aware of and which remained a major influence upon him throughout his career. A synopsis of the film will help us here: Ed Avery is a schoolteacher who moonlights in the evenings as an operator at a taxi firm in order to support the suburban lifestyle that his family enjoys. His life seems to be the realisation of the fifties American dream. One evening he collapses, is whisked to hospital and quickly diagnosed with a terminal condition whose only cure is a new drug which is still in its experimental stage, the painkiller cortisone. Avery and his family are warned that this drug has side-effects, one being a risk that it could lead to erratic behaviour. Faced with the choice between certain death and cortisone, Avery takes the drug and so begins his change.

The film’s script is based on an article by New Yorker staff writer Berton Roueche, warning about the dangers of cortisone. His story was adapted into a script, and Bigger Than Life was released almost a year to the day after the story’s publication.

So to begin with, if we look at Fig. 1 from the film, we see a broken mirror, a favourite icon deployed by directors of this era to depict derangement, a fractured personality, and mental instability.

Another famous example of this can be seen in Orson Welles’s The Lady of Shanghai (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2

In Bigger Than Life, this is given an extra twist when we consider that it is the mirror to the medicine cabinet which is shattered by his wife, exasperated by the demands of her husband. The cortisone is affecting him, bending his personality and he has changed from the aloof, yet cheerful and seemingly content figure we see at the beginning of the film, to something much more sinister. Indeed, Bigger Than Life was released in France, Italy, and Spain as Behind the Mirror, which is in direct reference to this scene. The implication here is that it is the cortisone which is behind the mirror, and it is this which is shifting his personality, a la Jekyll and Hyde.

The aloof figure who is presented at the beginning of the film, before he has taken the cortisone, as being dissatisfied with suburban life, socializing with bourgeois middle-class colleagues and ‘keeping up with the Joneses’, to quote the film, is unleashed as a menacing tyrant who terrorizes his family and local community with paranoid hectoring and eventually a blood-lust which sees him come close to committing filicide. The question which divides critics then is this: has the cortisone completely transformed Avery, or has it unleashed some part of his personality, a drive perhaps, which has lain dormant, suppressed by the social glare and the pressures of the American culture in which he lives?

Discussion of another pair of images can also help answer this question.

Fig. 3

In Fig. 3 we see Ed with his son Richie and his wife Lou in a gloomy scene in Ed’s study. After missing lunch as a punishment for not catching an American football pass, Avery’s son Richie struggles to complete a maths problem. His father tells him not to get flummoxed, and implores him to ‘use his reason’ to work out the calculations. He will not allow the child to eat his evening meal until he has completed the work set for him. We see Barbara Rush, as Ed’s already beleaguered wife Lou, pleading with her husband to let the child go. What is interesting here is Ray’s use of the low key light which creates the long and menacing shadow behind the actor playing Ed, James Mason. It casts a long shadow on the door behind. Ed’s shadow is big and looming, dwarfing that of his wife. We see the child, Richie, right at the front of the screen, making him seem disproportionately small.

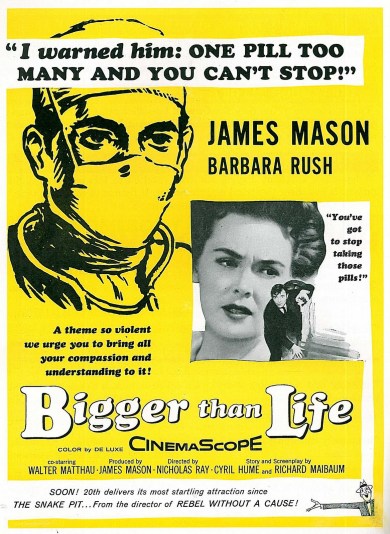

Indeed, size is often used during the film, both in terms of image and text: note the scenes in the garden in which the father and son play American football, and in particular the shot in which Avery, in what the filmmaker Jim Jarmusch describes as being a ‘disgusting’ shot, towers over the school, taking up the whole of the screen. In the lead up to this shot, Avery tells Lou, who drives him to work on his first day back at school after being hospitalised, that the first sight of her and his son after he regained consciousness at the hospital made him feel ‘ten feet tall’. Apart from the obvious name drop of the Berton Roueche article that the script to this film is based on, this scene is significant because it seems to suggest that the sense of superiority which comes to manifest itself later on in the film is already a deeply rooted feature of Avery’s personality. It also seems to come with his status as the male patriarch in the nuclear family. In the poster in Fig. 4 below we see the corny tagline by the face of the medical practitioner saying “I prescribed it…He misused it!’ This could easily lend anyone to think that they were watching a moral panic tale like Reefer Madness (see Fig 5), however Ray’s clever insertion of this shot before Avery starts to overdose on the cortisone poses the question: has the cortisone completely transformed Avery, and if not, why does he become what he does become as the film progresses?

Fig. 4

Fig. 5

This has split critics, and which way one goes will affect how one sees the film: if one thinks that Bigger Than Life presents us with a melodrama, one which tries to warn us that even the most honourable pillars of society can be warped into hideous monsters thanks to taking drugs, then so be it, I will not disagree with this, on one level at least. On the other hand, the change in Avery’s behaviour can be seen as something which is always there, the sickness he feels is a malaise brought on by a culture which celebrates mediocrity and is paranoid of the other, one which does not subscribe wholeheartedly to the sort of consumerism which characterized this decade. The cortisone has simply served to amplify this frustration and unfettered it from his emotional ties to his family and to the economic ties to his profession.

Finally if we look at Fig. 6 we see Ed Avery in a state of delirious happiness after cheating death thanks to the ‘miracle drug’ cortisone. He takes the family shopping, and splashes out more than the family can afford, spoiling his wife and child in a frenzy of consumer spending.

Fig. 6

We have previously seen Ed worry about the family’s finances to such an extent that he has taken up a second job moonlighting as a telephone operator, yet here we see him spending money on expensive clothes by Christian Dior and Jacques Fath. This is after he has forced Lou to parade up and down in dresses he has selected. Visibly uneasy with this false display of wealth and expressing reservations about the purchases, Ed exercises economic power over her by asking her to ‘remember who is paying for all this’, and we see a blatant exertion of his economic and social power as the patriarchal figure in the family. However, in this instance, and in much the same way as in the scene described in Fig. 3 above, we see Lou challenge Ed. I think that this is interesting because it shows that the previous power which Ed inevitably had as the patriarch in the family is only challenged when it is exerted to despotic measure. In the daily life of the family this power goes unchecked and unchallenged, allowing Ed to be the dominant economic force out of him and Lou. It also allows him to make the major decisions for the family. It is only with the taking of cortisone, and the emergence of a socially unacceptable form of power that this is flagged up. Therefore the drug acts as a catalyst which warps his behaviour beyond socially accepted norms of power.

The results of the drug upon Avery’s behaviour are interesting to think about, and perhaps can serve to show us, as viewers, how we are trapped, or to be more optimistic, kept sane, kept from performing monstrous actions on the ones we love, our contemporaries and our colleagues, by our ties to the community in which we live, be they emotional and/or economic ones. Perhaps the jargon of authenticity that blights some existential works can lead to a belief in a chimerical realm of genuine existence which in fact merely brings suffering and wreaks a path of destruction, a rejection of all that fails to shape to a, by necessity, nebulous and ill-defined realm of the authentic, genuine, or true way to live.

However, here’s the sting in the tail: is the drugged Avery completely wrong? Are his criticisms of the church, the education system, and his society the ravings of a cortisone addled mind? I’m not sure. While his character becomes an arrogant tyrant, he is at the same time charming and even charismatic, an anti-hero whose ridicule of the church is comparable to Marlowe’s Faustus. He is an ambitious intellect, dissatisfied with those around him who seem to be content bumbling through life with no aim other than to work and gain pleasure in their spare time. Should we vilify him for taking a drug which enables him to think he is a king amongst men, and gives him escape from his dreary existence as an underpaid schoolteacher? This is one of the many questions that this film poses, questions which have no simple answer and questions which make Bigger Than Life a rewarding film, a film which stands up to repeat viewing more so than much of the cinema produced in the sunset of the Golden era.

Kevin Jones

References

Andrew, Geoff. The Films of Nicholas Ray, Charles Letts and Co, London: 1991

Deleuze, Gilles, Cinema 1: The Movement Image, trans. Hugh Tomlinson, The Athlone Press, London: 1997

Eisenschitz, Bernard, Nicholas Ray: An American Journey, Faber and Faber, New York: 1992